Aaron Frank will accept your offer of a trip to Paris.

Aaron Frank will accept your offer of a trip to Paris.

All too often, new music is judged on back-story rather than its actual quality. Obviously it’s the critics’ job to separate music from myth, but occasionally, you come across an artist whose music is as interesting as its creation process. A good back-story can sometimes add an addendum, offering context for lyrics and overall production.

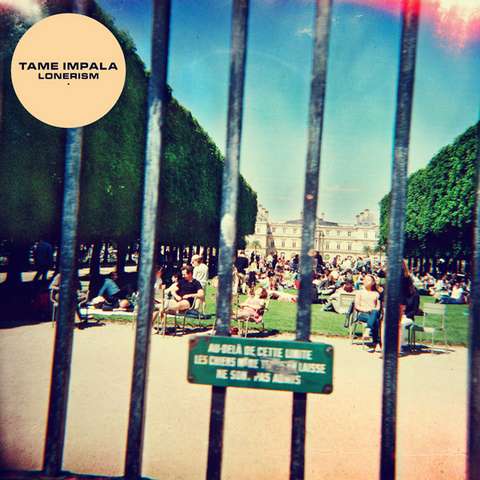

Prior to the release of Tame Impala’s second album, Lonerism, a teaser trailer and press release made the rounds, explaining Parker’s decision to write the new album alone in Paris, instead of his native Australia. Based on the expansiveness of Lonerism’s production, you get the impression he sustained himself on a healthy diet of Serge Gainsbourg, Air and good French wine. During his time in Paris, he also produced and played guitar on the debut from French psych-pop band Melody Echo’s Chamber.

Being alone in a strange new city is one of the most creatively invigorating experiences a person can have. Distractions are limited; your family and friends are thousands of miles away, and basically all you’re left with are your thoughts and passions, which end up being tools for survival. Your thought process is also less clouded and especially in Parker’s case, you end up generating some of your best ideas.

Psych-rock has a history of being distinctly abstract, particularly in the lyrics, but Parker’s heart has never been more on his sleeve than on Lonerism. The stripped down instrumentation and lo-fi production help to mirror the more intimate, personal appeal — represented in the lyrics — which are mostly about being an isolated romantic in a shallow age of social media and the age-old struggle of coming to terms with your ture identity. Adding an entirely different angle, the two concepts seem to be expressed in the context of trying to save a relationship.

During first single “Apocalypse Dreams,” there’s a break at the three-minute mark, where you instantly feel like all of the air has been sucked out of the room. It’s a weird transition from the candy-store pop of the song’s chorus and the more jam-heavy section, but it’s the perfect way to capitalize on the song’s building suspense. “Apocalypse Dreams” is really just a song about being in love at the end of the world, but for an album filled with such anxiety in the lyrics, it’s worth noting how relaxed the songwriting comes off, particularly on “Mind Mischief” and even on the second half of “Apocalypse Dreams.”

But the comforting feel of the woozy jam-session on “Apocalypse Dreams” stands in stark contrast to the insecurities expressed in the lyrics. Later, on “Music To Walk Home By”, Parker laments, “In so many ways, I’m somebody else. Trying so hard to by myself.” It’s an instantly relatable concept to anyone that’s ever gone through a quarter-life crisis, but it’s worded so sincerely that anyone who’s been lucky to avoid such a thing can still feel the struggle.

The only real glimpse of bravado on Lonerism comes in the third-person on “Elephant,” a short, but hard-chugging nod to psych-forebearers like Black Sabbath. With a sound made unmistakable by spooky synths and background whispers, “Elephant” has somehow managed to become the hallmark of the album, recently commanding a remix by prog-rock innovator Todd Rundgren. The lyrics tell the story of unapologetic badass, who “rips the mirrors off his Cadillac, because he doesn’t like it looking like he looks back.” It’s not as if the narrator idolizes the subject, but you get the sense he respects his courage and unflappability, a metaphor that aptly sums up my feelings on Juggalos, among other counter-culture figures with questionable motives.

By far the most distinct and innovative song on the album is “Nothing That Has Happened So Far Has Been Anything We Can Control,” which sees Parker experimenting with more abstract composition. Up front, it seems like a straightforward echoey pop jam, before the music fades to dialogue where a friend advises, “Nothing has to mean anything.” Seconds later, the music slams back in and somehow you feel like the narrator has achieved closure in his existential crisis. It’s a very zen moment in an album filled with struggles and insecurities.

On Lonerism, Parker encapsulates the transformation from troubled adolescent to respected artist. Coming to terms with a creative outlet like music or writing being your future can be a difficult process, but adapting to the lifestyle can be just as troublesome. In reality, Lonerism is actually the perfect term for the type of philosophy one has to embrace when working in a relatively isolating creative field.

Kevin Parker was once a dedicated engineering student, whose father told him music was better suited for a hobby. Self-recording his own music since age 12, you’d figure he could convince himself otherwise, but it took a record contract and a successful debut to finally confirm it. With those two things finally behind him, and some well-spent time working with Wayne Coyne, Lonerism finds Parker fully indulging his purest creative tendencies.

Watch: