Art by Shelly Prevost

Abe Beame is never over the line, dude.

“But now I was haunted by a vision of… He was horrible. The lone biker of apocalypse. A man with all the powers of Hell at his command. He could turn the day into night and lay to waste everything in his path. He was especially hard on little things-the helpless and the gentle creatures. He left a scorched earth in his wake befouling even the sweet desert breeze that whipped across his brow. I didn’t know where he came from or why. I didn’t know if he was dream or vision. But I feared that I myself had unleashed him.”

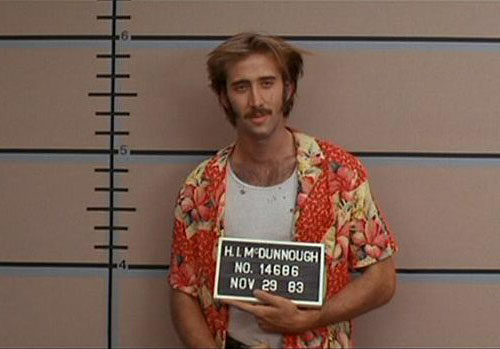

-H.I. McDonnough, Raising Arizona, 1987

The quote above is credited to Herbert McDonnough, he’s describing a nightmare. In it, a silhouette rides through a desert. He has tattoos and a grizzled beard, a force of wanton destruction, with a particular hard-on for the innocent. McDonnough dreams the villain Leonard Smalls into his film, and the Coen Brothers found a theme they would pursue for thirty years.

Raising Arizona is the second film by Joel and Ethan Coen. It is wildly inventive, animated with screwball humor and a big heart. It is grounded in technical mastery, brimming with a film nerd’s studied winks and God-like wizardry that most great directors aren’t capable of. Arizona was the birth of their style. And it starts with their villain Leonard Smalls.

Though he is lended mystical trappings and superhuman power, Leonard Smalls is very human, subject to greed and avarice. He’s introduced and represented as more symbol than character, but there’s a semblance of motive in the text. It’s a very understandable decision made by two young screenwriters, as is their decision to award Nicolas Cage’s McDonnough a triumph over Smalls, and in effect, evil. He pulls the pins on a string of grenades on the demon’s absurdly weaponized person. Smalls doesn’t realize until it’s too late.

Leonard Smalls wasn’t the Coen’s first heel. That distinction belongs to M. Emmet Walsh’s slithery private detective in their debut film Blood Simple. The important distinction is that Smalls isn’t a man, he’s a biblical allusion, a corrective force in the universe, the boulder that threatens to roll you down hill, the gravity provoking it. He’s darkness, brought into the story with little logic or reason, no backstory and no real goal beyond spreading misery. He is a Deus ex machina.

The deus ex machina, a writer’s crutch that dates back to ancient Greece, is defined today as an unearned, unexpected resolution to a problem in the narrative. It means, literally, “God From the Machine”, and the implication of the definition is that divine intervention is a force of good, a miraculous conclusion, a happy ending. God descends to preserve good and smite the wicked.

There is another term, Diabolous ex machina that is used as the inverse. It’s an unexpected dark turn, an upperhand gained by the villain when least expected. While the deus ex machina is the hail mary thrown by many a writer who paints themselves into a third act corner, the diabolous is often a force employed in the second act, meant to propel the narrative with a sudden dark twist. A viewer of the Coen’s films might be tempted to argue the devices are seen by the brothers as one in the same, and together, they have radically changed the way the device is employed.

Over the next twenty years, the Coen’s were not wanting for bad guys: John Goodman’s monstrous sociopath in the divine comedy Barton Fink, John Tutorro’s weasel in Miller’s Crossing, and, with the exception of Frances MacDormand and her screen husband Norm, you could argue there were no redeeming characters in Fargo. But these characters are just that– characters. At times they serve purpose in the narrative, but they watch shitty TV, they drink, they tell stories.

The next Coen deus ex machina was Aloysius, a shadowy janitor who plays henchman to Paul Newman’s gleefully callous boardroom shark in The Hudsucker Proxy. The modern fairytale was a collaboration with Sam Raimi (credited as a co-writer), and you can feel that director’s distinct heightened absurdity in an art deco late 50s Hollywood studio recreation of New York, complete with a Bruce Campbell cameo. The presence of the silent Aloysius, and the film’s narrator Moses, two competing forces of good and evil that preside over the story, are distinctly Coen inventions. They alternately contribute obstacles and helping hands that push the narrative along, waging a climactic battle in a sky scraping clock tower with the fate of the characters at stake.

Fargo is rightfully hailed as their masterpiece. At the outset we’re told it’s based on a true story, but it isn’t. Helle Crafts was murdered by her husband in Newtown Connecticut in 1987. Craft discovered her husband was cheating and began divorce proceedings. He killed her and disposed of her body using a wood chipper. That’s about as much as the Coen’s specifically had to go on, with bits and pieces clipped and pasted together from the papers. With the trappings of reality stripped from the narrative, we can see the Coen’s forming a kind of philosophy within the confines of Fargo. Their inhabitants of Minneapolis shuffle through eternal winter, masking disappointment, pain and existential sadness with bone chilling cheer. Their little dreams and plans all ultimately come to nothing. They’re American. What’s crucial is the hint of lingering melancholy they allow to creep into their final sentiment.

In 2006 they made No Country For Old Men. The antagonist Anton Chigurh is a character conceived in a Joel Coen nightmare and born on Cormac McCarthy’s page. McCarthy is a natural muse for the Brothers; it’s surprising it took them twenty two years to adapt him. He is similarly fascinated by the roots of American evil. Chigurh is a classic McCarthy villain in the vein of the Judge Holden, a giant, hairless demon incarnate whose main objective in the story is spreading death. Chigurh is an utterly ruthless, enigmatic bounty hunter who kills nearly everyone he comes in contact with but lives according to his own ethical code that has a kind of perverse logic.

Crucially, we get less of Chigurh in the Coen’s version of the story than McCarthy’s, less explication, less motivation. On the screen, Javier Bardem plays him as a cold fish, all wooden mannerisms and funny haircut, like an alien who assumed the body of a human and is doing his best to act normal. In the end, Chigurh not only triumphs over Llewyn Moss, the compassionate hero of the story, he makes good on a promise and kills his wife.

Bardem would win an Oscar for his performance as Chigurh but for the Coen’s he seemed to mean much more: a breakthrough of sorts. They were able to tell a bleak story in which a protagonist isn’t necessarily undone by his own folly (though Llewyn makes his share of mistakes), but is simply beaten by a greater force of darkness. This time, Leonard Smalls wins. The movie tells its dark story, drops the mic and shuffles of its mortal coil, leaving us to decipher it as we will.

We’ll briefly jump ahead to Inside Llewyn Davis, the Coen’s sixteenth and most recent feature about a musician in Greenwich Village on the cusp of Dylan’s revolution. The Coen’s found a subject matter that allowed them to explore their pet themes and shed light on yet another musical tradition with American roots, so it’s no suprise the film is a masterpiece, but it’s the most quiet and challenging of the bunch on their resume. Davis, very loosely inspired by Dave Van Ronk, surveys his bleak Bohemian existence, and at a crucial juncture, takes stock of the number of paths he can pursue with his life. There’s domestic bliss, compromised workmanlike success, superior hedonism, joyless stoicism, and the looming threat of infirm senility.

The film introduces us to these paths and continues moving, Llewyn is understandably not eager to choose any of them because none are presented as attractive. What is revealed in the film’s final moments [SPOILER ALERT BEGINS] is that we haven’t been moving forward but looking back. The last scene in the film brings us back to the very beginning, with one crucial detail omitted from our first walkthrough. It’s the night of a performance at the Gaslight by Bob Dylan, one that would make him a star and destroy Llewyn’s way of life.

By saving this detail for the end, the Coen’s deliver a gut punch that takes a little time to make impact. We spend much of the film wringing our hands over the competition on the scene in Greenwich. We worry about his relationship with Jean and the impending abortion he has to raise money to pay for. We hope Bud Grossman will see something in him at the Gate of Horn. We hope he’ll find some peace, coping with the suicide of his former partner. Very little of this happens, but with the Dylan performance we realize very little of it matters. Llewyn’s entire way of life is about to be wiped from existence, as Dylan will use New York’s folk as a launch pad to iconic global success. Tthe Greenwich Village, and folk will become a sort of heavily commercialized bourgeois hell we know will destroy whatever desire Llewyn had to be a part of it. [SPOILER ALERT OVER]

In many ways Dylan is the deus ex machina here, but unlike Chigurh, despite being human, he’s not a character. He has no ill will for Llewyn or motivation to harm him in anyway. But the way the Coen’s depict him, in silhouette and unseen, heard in a grainy recording as Llewyn walks slowly toward the back exit to what we know will be a final ass kicking, he’s Revelation, he’s history, a force of nature.

It’s not the first time the Coen’s used a deus ex machina in this manner. In 2009, they made A Serious Man, a film that can be viewed as a kind of Rosetta stone for their themes. The movie seems to be channeling their childhood as Jews growing up in a gentile Midwestern hell. It’s also a fairly explicit interpolation of the Book of Job, as a decent man seems his entire life come undone, through little of his own doing.

The bulk of the film sees its protagonist, Larry Gopnik, an intellectual schlep, dealing with the seemingly endless string of personal, professional and financial hurdles thrown his way, with the doom of a doctor’s impending diagnosis looming over the story. A shaggy dog on the very subject of meaningless planted in the middle of the film ironically seems to be the “moral” of the story. Looking for meaning in the shit that happens to you is a human construct, little more than attributing meaning to shadows cast on the wall of the cave. In the final moments of the movie, the point is made by a huge, black, menacing tornado en route with Larry’s son at school. It’s the Coen’s most powerful and emblematic deus ex machina: an uncaring, unfeeling force of nature that needs no reason to appear, a literal finger of God that will destroy anything in its path.

Like the force of God in their films, the Coen’s are getting further away from the mortal trappings of their stories. Plot, resolution, character development, message — these elements still exist in their films but they’re becoming increasingly abstract and removed from the proceedings. A shade of increasing melancholy influences their work, even as they continue to laugh into the cosmic void. They’re using Leonard Smalls, Aloysius, Anton Chigurh, Bob Dylan, and a tornado to make a simple point: Make your plans, dream your dreams, enjoy your movies and books, it will all be undone. One day, you and everyone you know will die. Deal with it.