Sean McTiernan has finally recovered from his battle with scurvy.

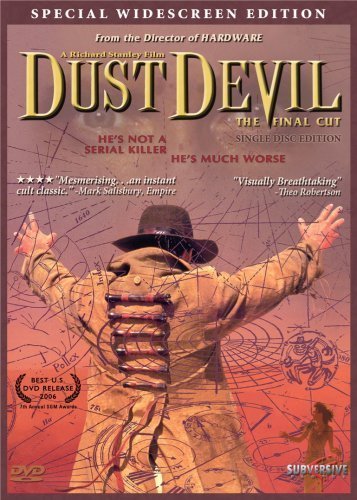

1993’s Dust Devil is a horror classic. We’re not even talking a surprisingly-effective-for-this-kind-of-nonsense, peep-immediately-if-on-netflix-instant classic like Deranged. We’re talking a work of art on the same level as The Thing, Chronos and There’s Nothing Out There.

It concerns an evil spirit that roams the Namib desert in the shape of an American decked out in Cowboy clothes. He senses people on the brink of abyss of misery, goes to them and pushes them in (using extremely complex ritualistic murder, of course). He is collecting souls so he can once again journey out of the physical world.

In the movie Dust Devil we see this evil pursue his next soul, a woman fleeing from her abusive husband. We also follow the detective who is convinced, despite the assurances of those around him, that he’s merely on the hunt for a regular old serial killer, not realising his growing desire to kill himself is drawing him inexorably closer to the Dust Devil.

An impressive concept sure, but the true glory here lies in the singular execution of Director Richard Stanley, who came to the project fresh off his underrated sci-fi slasher Hardware. At the time he presumably had no knowledge that his writing of the big-budget abortion that was to become the Island Of Dr Moreau would sink his fiction directing career forever, making Dust Devil effectively his last hurrah. And yet still, what an incredibly effective hurrah it turned out to be.

Dust Devil has one of the best opening twelve minutes in horror, telling you not only all you need to know about the characters, the setting and the look of the movie but also the limits of cinema full-stop. It’s an inspiring opening salvo of visual flair and stylised violence. It sets an impossibly high standard that Stanley continually and nonchalantly surpasses for the remainder of Dust Devil’s running time.

Be forewarned, there’s enough symbolism, allegory and metaphor in this movie to fill at least 4 Pharoahe Monch albums. Much as I like Monch, that’s not exactly a compliment either. One of Dust Devil’s weakness is that at any one second it could be one of roughly five movies that seem to be wrestling for dominance.

There are scenes where the intent is pretty clear such a when a white South African accidentally ventures into a Namibian bar full of black men and gets beaten up by a man who asks “Do you believe in God, South Africa? Yes? Well maybe God can help you”.

However the explicit political message really jars with the Tarkovsky-jacking dream logic that the movie operates under, the vision quest of the man investigating the Dust Devil murders and the purposely-half-baked love story between the eponymous demon and his chosen “victim”. It’s rarely clear what type of movie wants to be until the third act which presents a definite and defiant headlong sprint into total insanity.

It can certainly be a muddle, but it’s an unarguably compelling one. There’s a very definite intent behind setting the movie in the Namib desert, aside from being based on the true story of a serial killer who roamed the lands for years committing ritualistic murders (he was eventually allegedly killed in a shoot out with police, although the recovered body had no head and evidence it was that of the killer was slim).

The twin protagonists of the movie, who only meet during the delirious finale, are a black police officer and a woman in a physically abusive marriage, both provide a damning mirror for the rampant racism and sexism in that part of the world at the time.

Though the politics are often a bit in-your-face distraction from the fascinating core concept of a demon that preys on those who call out to be victims, they are often as biting and shocking as anything the more fantastical elements of the movie have to offer.

There was a lot of creepiness and dream logic going around in horror movies in the 90s. I’m not sure if it’s fair to blame David Lynch and Clive Barker for all of this but it’s always good to blame something on Clive Barker so let’s go ahead and do that.

However, unlike most of its cinematic contemporaries, Dust Devil wields its sharpened blade of unreality and mysticism with atomic precision, slicing conventional logic in many deft and interesting ways.

In fact in comparison, most other bizarro horror movies come with it like someone who has never played Tekken before getting their hands on Yoshimitsu. They’re definitely holding the sword but they’re still just throwing out the same wild-punchy bullshit as everyone else and, more often than not, they’ll panic-mash all the buttons and accidentally use the sword to kill themselves.

I’ve said if Dust Devil were a song, it would probably be “Mind Playing Tricks On Me” by The Geto Boys. And while this still makes a sort of sense, it’s also not really true. Because Dust Devil manages to sum itself up perfectly in the too-brief scene where The Dust Devil and Wendy Robinson dance.

Most of the movie’s soundtrack is the kind of atmospheric-tones-and-whooshing that can be found in many movies around that era, especially anything that wanted to convey the kind of eeriness Dust Devil provides a masterclass in. Although much of this is better executed than most soundtracks of this type, mixing with natural sounds and making the bizarre narration even more effective, it’s far from perfect. The opening and the credits music both sound like the kind of thing you’d play over helicopter shots over of South Africa to try to get people to fly there and spend money. It really is a jarring that such slabs of cheesiness bookend a film that otherwise hits precisely the right mark between mysticism and brutality.

Although there are several digetic pieces of local music throughout the movie, it is the one that appears from nowhere that captures the mood of the movie so perfectly you can forgive the other missteps. You have to hand it to Richard Stanley, to have one piece of recognizable music in a movie is a fairly common tactic, but it’s rare for a choice to seem so counter-intuitive, so misjudged, and yet have it slot so perfectly into the world he has created that it feels like it’s being summoned up from the guts of the film. Yet that is exactly what happens when Hank William’s Ramblin’ Man wafts its way in to Dust Devil.

On the surface, putting an old country song in a horror movie set in the desert seems like a blandly obvious choice. In the simplest terms possible, the movie is a horror riff on the Western genre. If you were simply told about it, it could seem like the same kind of “we have A, let’s just throw as much B at it as we can, I guess” methodology that made someone think the only thing more badass than putting a Rob Zombie song on the soundtrack to a hillbilly slasher was to put the motherfucker in the director’s chair.

Initially one might be shocked Stanley didn’t plumb for something a little more local, considering how vital the setting is to the fabric of the story. His choice is odder still when one considers Stanley’s only previous cinematic release, the 2000AD-influenced cyber-punk horror Hardware, actually had a substantial cameo from a member of uber-goths Fields Of Nelphlim. Considering this, it’s shocking he didn’t settle on any one of country and goth’s excruciating intersections to set the mood for Dust Devil. I’d love to say the omission of a track like this gives the movie a timeless quality but I can’t. Any aspiration of timelessness is defeated by a middle-class, white South African man’s casual rocking of a purple, luminescent shell-suit, the like of which Husalah might resurrect if he was doing a sequel to Hustlin Since Da 80’s and felt he needed to outdo the original’s high-top fade.

In any case, it’s justifiable to assume using a Hank Williams song in a movie of this type might appear weirdly-obvious for an idiosyncratic auteur like Stanley. But once you really listen to Ramblin’ Man, examine the context in which it appears and how closely its approach and execution mirror Dust Devil, it’s clear that it wasn’t only the best possible song for the scene, but that the two combined only serve to bring the oft-ignored primal-oddness of that era of country music to the fore while also summing up the movie in a neat, spooky way.

It’s tempting to claim this is all about context, that the movie elevated what would have been just another country song. It’s plausible to posit merely having lyrics about a wandering stranger prompted the song to be dropped in to Dust Devil with the same headbutt-obviousness that lead the Wackhoski brothers to end The Matrix with a song by a band called Rage Against the Machine (they may has well have unfurled a giant banner reading “Does everyone get it?” and then ridden off into the sunset on a motorbike made of leather, extraneous straps and money).

But once again, even a cursory listen to the song in the context of the movie should put any of these fears to rest though. Right from those opening chords, Ramblin’ Man doesn’t merely feel like it was made for the world Dust Devil inhabits rather it seems like the world was constructed around it.

There is a deep sadness in many old country songs. There’s plenty of rousing stuff too, and much of that is great (and about Jesus). But the real, lasting power lies in the stuff that expresses some elemental, almost-psychotic grief. It’s easy to make fun of but once you realise how sincere much of it is, it can be truly disturbing. A small meme on the Internet was the cover of the Louvin Brothers Satan Is Real. While the cover is certainly ridiculous, even more so when you consider the had to actually build that stuff for real and light that fire, the intention behind it is very serious indeed.

Think of how intense it is that a pair of dedicated Baptist brothers, one of whom was an alcoholic with multiple failed and abusive marriages, wrote a concept album about Satan being a real thing that was trying to destroy them. I like noise music and at least 45% of the metal genres of which I am aware but nothing has ever approached the rawness of these two tortured dudes calling an album Satan Is Real.

The Louvin Brothers were incredible singers both and no matter what they sing about, be it Jesus or sadness (they often sing about both at the same time), they did it like pained wolves. Their work together and as solo recording artists is worth a listen, start with any album you find of a particularly religious bent.

Hank Williams, though, is one of the undisputed master of country sadness. He’d stand on stage dressed in a suit, make some polite stage banter and then sing the bleakest songs imaginable in the manner of a ghost. His definitive biography is called Sing A Sad Song and most of his best known numbers consist of plaintive odes to universal sadnesses. They are simple songs which often strike a compelling balance between struggling to put an overwhelming sadness and finding the perfect nail to hit a particularly grisly nail square on the head (nothing is fucking with “Your cheatin’ heart will tell on you” for gut-wrenching sentiment…not then, not now).

If one is so inclined, there’s plenty to mythologise about Hank Williams’ death. Williams died of a heart attack at the age of 29, after a year when morphine and alcohol all but destroyed his career. He died in the back of a car on New Year’s Day 1953. 15 years later Williams’ son, dressed in the trademark suit, released a cover of one of Williams’ famous songs Long Gone Lonesome Blues and then spent the rest of his life trying to escape his father’s shadow. `It’s a grim tale of southern gothic that they genuinely do try to step around at the Country Music Hall Of Fame in Nashville because, even for country, it’s just too damn tragic.

But despite how crazy that all sounds, the music doesn’t really need it. The mournful, sad end of country music is at a level of sadness and strangeness that far outstrips that 27 club rubbish. It’s also important to note that country isn’t only good because it’s being sad and bleak, it just does it particularly well. So well, in fact, that it can even imbue Neil Young’s belly-aching about the times his assholesness actually manages to outstrip his talent with gravitas and sweet sadness.

Untitled from No Chorus on Vimeo.

This elemental misery is perfect for Dust Devil, a fractured movie about broken people. The song even mirrors the movie, outwardly a simple enough spin on a familiar tale but when you look past the lyrics to the delivery, there’s something more ancient and bleak at its core.

Not only that but through the story of being a restless rambler, Hank Williams howls like an animal. Another easy parallel to draw but one Stanley is clearly aware of. The subtle predatory nature of the dance the Dust Devil does is made exponentially more sinister with every passing elongated note and choked texture of the comes from Hank Williams’ mouth.

Those aforementioned distinctive opening bars of guitar are so delicate and spindly transcend country and recall the music heard in classic later period noirs like Sweet Smell of Success. Appropriate as, setting location aside, police officer Ben Mukurob’s search for the Dust Devil is the stuff of classic noir. He’s got a tragic past, the classic hat and coat and a disregard for those around him. He’s also kind of a ornery dickhead and has to come to terms with part of his culture he has repeatedly rejected. It’s all so noir, it’s surprising he doesn’t find time to throw a few slaps at Peter Lorre (although when you consider the sangoma Joe Niemand’s sneaky demeanour and hard-boiled take on witchcraft, talking about coming at the Dust Devil with “fists full of knuckles”, maybe he’s meant to be the Lorre surrogate). Ramblin’ Man’s extra-Third-Mannish opening zings are a subtle but welcome nod to this part of Dust Devil’s stylistic heritage.

There’s something primal about the intersection between those haunted-house chords and Williams’ ghostly voice, some particular power that’s more prominent than usual in Ramblin’ Man. This hasn’t escaped Hank Williams’ punk-inclined Grandson Hank III who covered the song with the Melvins.

Known for sounding spookily like his grandfather, Hank III and the Melvins played it straight, making the spidery, supernatural feel of the original even more prominent. Of course, being the Melvins they went ahead and recorded a cover of Merle Haggard’s anti-hippy jam Okie from Muskogee, seemingly to make up for such a reverent cover. It’s telling though that the Melvins, great fans they are of the sinister and the eerie, were so reverent to Ramblin’ Man. They knew all the ingredients they needed were there already. Mark Lanagan, The Residents and Cat Power have all done their own versions of the song as well and presumably they too have recognised the weird, twisted soul the song projects so effortlessly.

Dust Devil’s a crazily ambitious piece of horror film making, one that deserves far more recognition. Not only does every inch of it feel new in a genre that even 18 years ago had a high risk of stagnant ideas and themes factored into the most hopeful new releases but it actually executes 80% of its weird ideas really well. All of this also has the decency to be wrapped in an effective game of cat-and-mouse that expertly uses the conventions of at least two genres.

And no better song to provide the calm before its storm that “Ramblin’ Man” by Hank Williams. No other song could tap into both the surface story and the underlying menace of Dust Devil so well and none of the numerous other versions could capture that same consuming sorrow that Hank Williams does with such disquieting ease.

Download:

MP3: Hank Williams-“Ramblin Man”