Dweez has no hard and fast rules but tends to read things only once.

Dweez has no hard and fast rules but tends to read things only once.

Until recently, I didn’t get vinyl. For all the evil it’s wrought on our attention spans, I am a champion of the ones and zeros. They’ve enabled my iTunes collection to swell and I change residential time zones enough for vinyl collection to be a non-starter. Or maybe it’s just that choosing analog over digital seemed like self-sabotage, especially when it came to new music.

Going to the store the day of a record’s release was something I used to observe with religious dedication. Many of us did. Not all the memories are warm and non-embarrassing — my rock-to-rap-road stemmed from utter disillusionment at 311’s From Chaos to complete obsession six months later when Nas released Stillmatic — but all the memories are mine. I own them. The crystal through which I can recall the day Kanye’s now decade-old debut dropped, is so clear that no amount of self-aggrandizing manure will ever be able to so much as smear stink on my recollection of how that album felt on the first few spins.

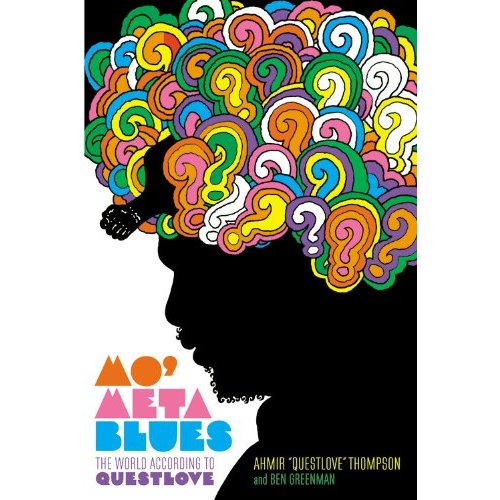

Romanticized or not, the feelings themselves are unmistakably glued onto every listen. That adhesive isn’t as strong when I don’t physically buy the release before the first listen. The point of this tangent is to tell you that my thoughts on vinyl have changed. While I was working on a documentary about Low End Theory, I was reading Mo’ Meta Blues: The World According To Questlove. And the day after finishing it, I bought Ras G’s Back on this Planet. And while listening to it, one passage stuck in my mind about the feeling of a first listen: “As you get older, feelings are hard to come by.” And this book produced unabashed emotions in me.

The Daily Show

Get More: Daily Show Full Episodes,The Daily Show on Facebook

What Works:

Ben Greenman, Rich Nichols, and Amir Thompson represent the offense, defense and special teams of Mo Meta Blues. They are the Seahawks. The traditional memoir form is the Broncos.

Credited as a co-writer, Greenman is a New Yorker editor and novelist. He’s no stranger to toying with text to get places prose can’t easily go. In Superworse, the novel version of his first book, he borrows from Nabokov’s Pale Fire to invent an editor who comments on the ongoing narrative in a forward, midword, and afterword. He brings the same strain of Meta to MMB to counter a form he considers “a highly synthetic narrative masquerading as something organic.”

Greenman tosses five different kinds of smoke in his strategy to defeat the traditional music memoir:

1. Q&As between Thompson and The Roots comanager Richard Nichols (although by Chapter 9 Nichols leaves the bold font and becomes a footnote soldier).

2. Editor & co-writer email correspondence

3. Narrative chapters

4. “Quest Loves Records” (in three parts)

5. Two color photo inserts

His email correspondences function as a kind of instructional manual. Reading about the book’s process as the book progresses, illuminates the nuance. This signage is not unlike the beginning of Dave Egger’s Heartbreaking Work of Staggering Genius, pointing out why this is all happening the way it’s happening.

Selecting as talented and lighthearted a co-writer as Greenman gifts MMB with all kinds of perks in the prose chapters. Thompson, even at his most artistically versatile, couldn’t keep the 274-page ride this scenic, all on his own. When you hire a pro like Greenman, you get more than the Meta.

The initial rave reviews for MMB focused on the terse tidbits of the Root’s co-manager. Nichols caught the eye of The Daily Show and the like for the way he chimed leisurely into the text only to deliver some serious dome smackers. That Nichols only contradicts everything Thompson says in a chummy back-and-forth is an oversimplification. Nichols’s commentary borders on the profound. He likens live music experiences to early man’s earthquakes and stampedes, he rues the absence of diversity in winning in the music business, he big-ups Kendrick Lamar and Frank Ocean as signs of life in the oft-mourned styles he’s spent decades shepherding Thompson & Co.

The dreadlocked Nichols, playing Greenman’s in-text commentator, brings quotables by the boatload. In just one footnote spanning pages 125-126 we get:

“Not to ya’ll: the Zeitgeist ain’t a fuckin’ bicycle built for two.”

“Hubris is such a slippery slope. When I get a whiff I’m inclined to pull out Occam’s Razor and hack my way through a nigga’s loftiness.”

“As for wishful thinking, well, that’s that shit I don’t like.”

It’s unclear how much of this is Greenman and how much is Nichols but the latter gets off on being underestimated so now matter who delivers, “I began to realize that hip-hop was something old, something new, something borrowed, and something blue,” everyone wins.

If the guy decides to write a book of his own, I wouldn’t bet against it eclipsing MMB in cliché destruction. Nichols is the Mo’ in the operation.

Anecdotes abound when MMB goes narrative. Origins are explained. Thompson breaks a salad bowl to keep his mom from overhearing Prince’s “Lady Cab Driver” raunch. Being mistaken for a street musician from an Spike Lee commercial inspires him to become one. His band’s first name is Foreign Objects. He rides in Nichols’s Flintstone’s-style station wagon to a gig.

These gems are crumbs on the bumpy trail. Quest details the Soulquarian utopia that crumbles, D’Angelo and Dilla quit making music for vastly different reasons, and he mulls over having to take a Princeton professorial post. Thompson worries, as every artist does, that there will never be enough commercial success to feel comfortable.

Did you expect an artist like Questlove to sell you short on the Blues?

“A quick lesson. When people think about blues, they think of personal music: a man reflecting on his hard luck with women or his disappointment at his own moral limits. They think of Skip James signing “Devil Got My Woman” or Robert Johnson worrying about the hell-hounds on his trail. But that’s not all it is. With apologies to Brother West, blues looked outward, too.”

Thompson then descends into the history of Blind Willie Johnson’s “God Moves on the Water.” The breakdown illustrates both the most immediate and likely the longest lasting reward from MMB: Thompson’s gift as music curator. Three separate and expansive “Quest Loves Records” sections tap deep into that talent.

What Doesn’t:

Inside a steel safe, above a leather-chaired corner office, in a manhattan sky scrapper there is a music memoir checklist. Despite sliding on the James Bond gloves for this memoir mission, the checklist proved impossible for an editor even as deft as Greenman to change. MMB stumbles over yesteryear’s presupposed memoir fodder.

Troublesome checkbox one: The Bust Back.

The book’s subtitle is: “The world According to Questlove,” so you expect to hear his opinion. You expect to hear the “artists side,” but back-and-forths, especially those aimed at anonymous critics seldom yield substantial progress of any kind.

“It’s clear to me that there are certain critics who feel that they can’t champion the Roots because it someone exposes them—and here I’m talking mainly about middle-class black writers.”

Fact or fiction, it doesn’t matter. Hearing a third-party talk about why an artist deserves more love is a tough sell, especially when it’s the artist doing it. You don’t have to destroy the ego to write a resonant memoir, you just have to wipe it a bit.

Troublesome checkbox two: The Near Past.

Greenman even warns of the book’s bigger misfire in his trademark meta way. He likens memory to the doppler effect as it pertains to the recent past.

“There’s less perspective and sometimes more of an almost physical discomfort. Losses are felt more painfully, failures still sting, confusion may not have cleared quite yet.”

There’s a standard to make an entertainer’s memoir as current as possible. It’s as if the memoir checklist guardians sky-write the question “Where are they now?”

Not only do MMB’s final chapters confuse — just as Greenman forecasts they will — but at one point, they even Bust Back troublesomely.

A half-dozen pages are spent clearing the air about this Michelle Bachmann fiasco with a recounting of official Twitter apologies and an attempt to recapture the suspense of a moment where The Roots almost had to resign as Jimmy Fallon’s official band. Like all recent mistakes, the explanation is murky and seems to only reopen a wound that hasn’t completely scabbed over yet.

These compulsions to adhere to the memoir checklist are forgivable. For all the fun here, MMB is a book made to move units not build bridges over the troublesome current inherent in the genre. Maybe that’s too meta a battle to fight. In a way, these shortcomings are no different than the role Questlove serves when he steps up to the DJ decks. Now and then, ya gotta give the people what they want — or at least what they expect.

But Should You Read It?

MMB has too many things going right to avoid. It’s shortcomings are peripheral in the greater run of play. The book is more than the sum of Nichols’s insight and Greenman’s tricks and Thompson’s taste.

Anyone who’s bought an album in a 3D store on the day it was released should read Mo’ Meta Blues. If that sounds like exaggeration, I offer an alternative. If the answers to even half of the following questions entice you, it’s worth your bucks:

“Where do I start?”

“What do you do when just listening to the music you love isn’t enough?”

“What’s the single most influential moment in the history of hip-hop?”

“What were we before we were the Roots?”

“Where were you when Kurt Cobain killed himself?”

“When was hip-hop’s funeral?”

“Are there hip-hop creationists?”

“How did I know we had finally made it?”

“How do you measure your own small life next to monumental historical events?”

“How do things get their names?”

“What’s the right way to react when your failure becomes a success?”

“How do you plan a rebirth?”

“Where were you when Michael Jackson died?”

These questions kick off each of MMB’s narrative chapters. The final chapter itself ends with twenty-three inquiries rammed together.

It’s a book with less answers and more questions.

On page 81, Greenman goes back to Nichols’ bit about albums and feelingsL “He was going a mile a minute, like he does, but at one point a silence swelled the line and Rich said, “As you get older, feelings are harder to come by.” It was so simple and poignant.”

Why, as we get older, are feelings harder to come by?

The ones-and-zeros firing off behind my minimally designed iTunes window are beautiful things. It’s efficient. There is power in the months of music at my fingertips. It feels right.

So what, then, is the point of vinyl?