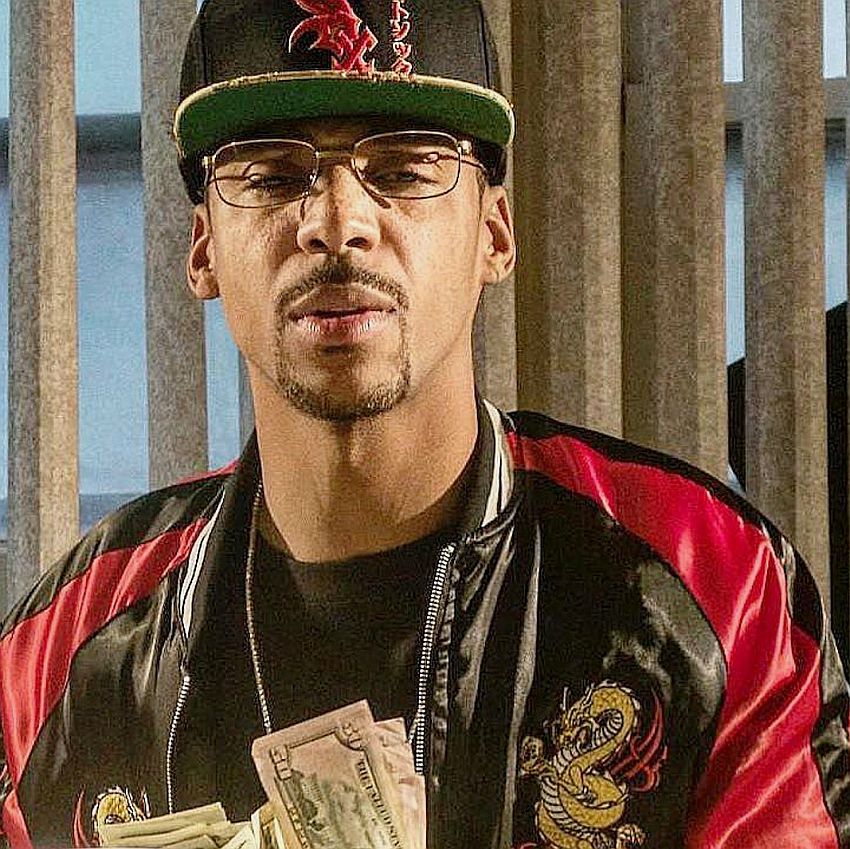

Boldy James has been elusive for a long time. The Detroit rapper’s presence looms over audiences and fellow MC’s like an ominous spirit. Immune from the pressures of fads and trends, he comes and he goes as he pleases, always at his own pace. Sometimes it’s on his own accord, and sometimes it’s out of urgency. Boldy’s unshakable allegiance to the people and the places that have shaped him isn’t necessarily singular, but his ability to effortlessly weave them in and out of colorful scenes littered with the residue of his city is. When Boldy preaches his street gospel, the stream of consciousness style brings an unfiltered account of all that can be seen outside of his car window during a long drive. The listener just so happens to be sitting in the passenger seat.

Born James Clay Jones III, the proud representative of Detroit’s East Side took in early just how dark and dangerous this world can truly be—and where he might fit. At the age of 5, his best friend was raped and murdered by her own brother. His cousin Ricky was also a victim of homicide. Later, he and a friend were used as makeshift shields for bank robbers trying to elude the law. Needless to say, Boldy’s life was far from “normal” during his formative years.

As these chaotic moments shaped the way Boldy saw and interacted with his surroundings, he was also shaped by a father who worked in law enforcement. With the absence of his mother, Boldy’s father served as his internal compass. His morals, his values, even his humility comes from his father. Yet his father still represents authority in so many ways. With the duality between home and outside, Bold was forced to retreat into himself and hide his identity in the streets from his father. But his innate musical talent began to emerge in a way that provided an outlet for a young man just trying to figure things out. And as he continued to run and fall and get back up, he would always return to the music. It was the music that always lived in him.

When his life had become entrenched in the street, the music served as an indispensable outlet; especially when shit got real.

After dropping My 1st Chemistry Set in 2013, Boldy would be on and off of probation for the rest of the decade. Even while remaining evasive to both the law and fans because of his shadowy activity, he continued releasing gripping and raw bodies of music like The Art of Rock Climbing and House of Blues. This pattern became indicative of the ups and downs within his personal life. Over an incredibly choppy period of self-imposed stops and starts in productivity, Boldly landed a deal with Mass Appeal. On paper the situation looked like a positive next step in Boldy’s journey. As the first signee to this Nas-affiliated label, the spectral Concreature had found a home, and a team that understood his obligation to authenticity, his stern, strident, minimalist sound, and could package it in a way that left all of the grit on the Warren Ave. representative untouched. The celebration was short lived. For as rocky as Boldy’s career continued to be, the quality of his albums remained high. Nevertheless, the music never truly resonated on the scale that Mass Appeal presented through its many announcements and press releases. Free of a deal or a label backing his career, Boldly went back to doing what Boldy does: hustling, eluding, and rapping in between the two.

February’s The Price of Tea in China arrived at the perfect time — not just for long patient fans but more importantly, for an anxious Boldy. Finding himself in another sticky situation that could send him back to jail, a call was made to his blood cousin, Chuck Inglish of The Cool Kids, and Boldy hopped on the first plane flying out of Detroit’s Metropolitan Wayne County Airport to California. After landing, he linked up with the legendary Alchemist, who believed in Boldy’s talent and potential, just as Boldy trusted in his legendary production talent. But this project was different, and the Alchemist knew it. It was during the mixing process that he began to feel that this was the tape that would really re-introduce Boldy James to those who may have forgotten about the veteran artist.

On a call after a few more trips from the D to Cali, Alchemist told Boldy something that had been long coming. All of the shit that he’d done in the streets. All of the pain and struggle he’d felt. All of the running was about to pay off. This project was going to wake some listeners up. And it did. With cryptic tales of street life on tracks like “Surf & Turf” featuring Vince Staples, and glimpses into the subconscious mind of an artist trying to escape an unfortunate fate on “Carruth”, The Price of Tea in China served as a re-introduction to the hazy, dreary world he’s woven over the past decade. Serving as a bridge between the Detroit of Dilla and the energetic, no brakes artist of now, Boldy’s smooth and conversational style allows for him to pull a listener aside, drop a gem or two, then drive down 7 Mile while taking detours along the way.

With The Price of Tea in China still soaring, Boldly dropped a surprise tape with fellow Detroit East Sider and film composer, Sterling Toles. Powered by organs and the floating notes of trumpets, sermons like “B.B. Butcher” and “Requiem” forced audiences to take notice as Boldy tapped into the spirit of Marvin Gaye’s “Inner City Blues.” Just when the masses felt as if they’d heard and seen more Boldy than ever before, he released The Versace Tape and announced a deal with Griselda Records. Both of these moments serve as affirmation of Boldy’s sole focus: to make the kind of music that represents his daily realities.

Some may attribute this newfound appetite for gritty, sample-driven, bullet-ridden raps to Roc Marci and Buffalo’s Westside Gunn, Conway the Machine, and Benny the Butcher, but over the last decade, Boldy has also dedicated himself to this sound. Thus, it makes this pairing all the more interesting. As a collective, they’ve built a movement that stakes claim to a very coveted place in rap. With them, all preconceived notions of what works in this new era of 808’s and club records has gone out of the window. And Boldy is prime to put the fear back into audiences who’ve begun to second-guess if their favorite rapper has been acting as a fictitious character this entire time.

At Griselda Records, Boldly is amongst his peers who, like him, have a desire to put reality first while breaking down the stereotypes the industry continues to peddle. The Versace Tape gave him the opportunity to play off of the brash Buffalo energy Griselda Records has harnessed while remaining the same veiled orator of the Detroit experience. Even in its artwork, the project presents a fashionable element that underlines Westside Gunn’s—and largely Griselda’s—attention to detail. The relationship rooted in the commonalities of their journey up to this point has Boldy finally feeling like maybe the turbulence is over. It’s hard to say if he’ll be able to truly stop but in this current place in time, at least he can focus on what’s directly in front of him; instead of missing the moment at hand. — TE P.

A lot of things come with the name “Detroit” in both the word and the name. For you, what does the word “Detroit” mean?

Boldy James: It means the city’s beautiful. It just means Bold and Beautiful. That’s what Detroit means to me.

Obviously, many of our sensibilities come from where we’re from. What are some of your earliest memories growing up in Detroit?

Boldy James: My best friend got murdered when I was five years old by her own brother. He raped and choked her to death. I remember waking up to a whole bunch of police lights and ambulance lights outside. I found out she had gotten murdered by her own brother. You know, that was some of my earlier memories. I remember dudes doing a bank robbery. They were running from the police and they tried to snatch me and one of my homes up to use us as a shield from the police, but we got away. I remember my cousin Ricky getting killed when I was younger.

You give pieces of this in your music, but I’m interested to hear what your family was like growing up.

Boldy James: I grew up with my pops but I didn’t grow up with my mother. My pops was an officer of the law but all my uncles, cousins, and shit was gangstas. So, I grew up different. I always had to keep a lot of things to myself and be private because I didn’t want my dad knowing what I was really into. I could have gotten into a lot of trouble with the kind of pops I had. So, I had to be a real smooth criminal type of nigga.

I know a cat that had a similar situation where his pop was really high up in local police but his family has real gangstas in. So, he grew up different and he had to keep certain things away from the home to try to hold onto that piece of normal—if you can call it normal.

Boldy James: I mean, my life wasn’t normal. I never had everything I always wanted but I always had more than enough. I wasn’t deprived but I’m not going to say we had it good or anything like that. My people used to disguise us being poor-middle class pretty good. So I was still a happy kid.

I also read something that said your family is also from the South. How much of that southern part of your family shaped your upbringing? Did you have summer when you went down South like most of us did?

Boldy James: Yeah. The family reunion was always down South. My dad’s mom moved down south when I was younger. The house that she moved out of she ended up selling it to my father. We went down to visit her often. I got in some trouble when I was 14 or 15. I’d just got out of juvenile. I had to go reform down there with my grandmom for 3 years. It was a court order that I wasn’t to return to the city until I graduated from school and walked my 3 years of juvenile probation down. I came to the city right before I got off probation and end up catching another fuckin’ case. So, I ended up getting in some more trouble when I got back home. But, down South was definitely an important part of my upbringing. My great-grandmother had 14 children by the same guy. They was based out of Mississippi.

I saw you saying in an interview that family is something that’s very important to you. You have your own kids. In fatherhood and in the larger scheme of things, what would you say is the defining quality of your family?

Boldy James: Me having a dad in general gave me those morals, values, and principles. It made me humble. It made me understand how important a father is in a child’s life. I didn’t understand it when I was younger but I started understanding it more as I got older, and started having my own children. It taught me the ropes.

I also saw you speaking about Detroit in an interview. You’re definitely one of those people that moves throughout your city. Every city has its different parts and everybody can’t go everywhere. What would you say your sides of town are known for? And why?

Boldy James: It’s Detroit. The whole city had bottomed out at one point. So, all the industry jobs was at a halt. People had to go on the outskirts of the city to find work. The city just developed into a lot of people hustling, surviving off the fat of the land. They ended up turning into people turf-warring and feuding over drugs. The city had blocks getting burned down from drug trafficking. I’m a product of growing up right at the brink of when it started happening. Like, I remember seeing all the houses down the block. Then I remember seeing the neighborhoods where they were stacked with blocks that had houses missing and shit. I remember the fires and the shootouts. Sometimes, if you had a bangin’ ass dope house the police would even burn that muthafucka down. I just grew up during that era. I’m a product of that shit. You know, the East Side I grew up on, Belvedere, East Warren is known for murder, drug trafficking, extortion—the list goes on. Then the West Side is pretty much known for the same thing. But there’s a bunch of bitches on the West Side. So, there’s a bunch of egos and that shit clashes. They both violent sides of town. I just learned to adapt and roll with the punches. It’s where a nigga from so I made the best of that shit.

Who would you say you started to look up to when you started to see these things change in your neighborhood?

Boldy James: You don’t understand how much you think the nosey neighbor from the neighborhood is being a burden when you tryna be half-ass nickel slick until you get older and you realize he was just looking out for everybody in the community. [They] always looked out for the elders. Made sure the kids got off safe from the bus to school. Those types of cats who give you the game. “Youngin’, pull your pants up.” Or, “Stop littering on your own street.” You know the person on the block who just keeps everybody in line. You don’t realize how important that was or the major role he played in the upbringing of you and the cats in your neighborhood. Because it takes a village to raise a child.

A lot of your music is dark and distant but I could imagine there are moments and times in your life like all of our lives where you just enjoy doing shit. What are some things you like to do that maybe people wouldn’t assume that you like to get into?

Boldy James: People probably wouldn’t think that I like to play ping-pong and shoot pool. They probably wouldn’t think that I actually know how to skateboard a little bit. [laughs] Like, that I can play ball really good. I like deer hunting. I like riding four-wheelers on the back roads. I like jet skis. I like real fast cars. I like racing. I like foreign women. I listen to a lot of music that a lot of people wouldn’t think I listen to. Music that I actually ride and vibe out to.

In knowing a few cats from Detroit and learning about the culture, Cartiers and Buffs are major pieces. Even the song “Pony Down” starts with a news clip talking about somebody getting someone for theirs. Can you break down for me what a youngin’ feels like when they get their first pair of buffs?

Boldy James: It’s like a kid who grew up with hand me down sneakers his whole life and finally gets his first pair or Jordans. Or like a kid who had a lot of material ready to record and it’s his first day in the studio. Or a nigga losing his virginity. [laughs] That’s damn near what it feels like getting your first pair of Buffs.

I also know you have to be a certain kind of individual to keep them and defend them because with someone like that where we’re from, other people want it.

Boldy James: Yeah. Because it’s a three-thousand, almost forty-five, sometimes five-thousand dollar pair of sunglasses. Na’mean? People take that as, “Shit. You just walking around with five g’s on your face?” That’s a easy lick. You know once we start accessorizing and putting Cartier diamonds in em and all that the price goes up. So, you have people walking around here with glasses as expensive as ten, fifteen, twenty thousand dollars.

I know, at least where I’m from, it’s easy when things can get heavy to have the street shit override the music. You’ve mentioned before while you’ve been making music and making your way in this that you’ve been dealing with a bunch of street shit. What was the thing that kept you coming back to the music?

Boldy James: I mean I’ve always done music—even between the street shit. So, no matter what was going on, up or down, all the between, I was always did and was going to music. I would rap for free. It just so happens I get recognized for this being my profession at this point in my life. I make a couple dollars off this shit but I make just as much money in the street if not more. It’s just a battle that I fight in my head. It’s just about growing up. I’ve never gave my daughter an actual job description to brag on what her father does when they ask her on career day what she wants to be or what her parents do. Now, I actually have a title. Or a label of what I actually do. You know, I’m a musician. So, she can tell them, “My dad is a musician.” Instead of sitting there playing guessing games wondering where this money came from or where the shit I do for her comes from.

Can you speak to that? Again, we keep going back to you being a father. Your daughter, and that connection that you two have, and now her being able to say what her pop does.

Boldy James: She pretty much knew that I didn’t have a job. But it’s different with my sons. I never had to hide anything from them. But my daughters I never let them see a lot. So, they probably played guessing games at some point. But, now they’re older and I don’t have to hide nothing from them. And it’s nothing to be ashamed of at this point either. So, it’s all good. It’s just something I went through as a Pops. You know?

In your journey, and it being one that a lot of cats can learn how to stay down, how to follow through, and remaining solid is there any advice you can give these young buls that are still dealing with what’s with very real situations while trying to have a career?

Boldy James: I just know you can’t do both. It’s going to eventually catch up with you and bite you in your ass. It’s going to prolong what you’re trying to do with your music career. It can be a hindrance at that point. I had some shit happen to me where it jammed me up and I had to slow down. I wasn’t able to move around the way I wanted to move to be able to get to what I wanted to get to, and do what I needed to do for my music to move in a forward direction. It was at a standstill because I was doing things that was putting my life at a standstill. If you can avoid it or if the money in the music overlaps the money in the street, you have to try your hardest to make that transition.

You’ve also been one of the more consistent cats throughout your career. When product drops it is A-1. I’ve seen you also say that you’re always trying to keep that bar where it is. What does longevity mean to you in this game?

Boldy James: It’s everything because you don’t want to be a fly-by-night type of nigga. Even though you’re older or your career is on some heading on the way out shit you want to be respected. You want people to think you’re cool and still support what you do as an artist. As a veteran, OG type of artist with some status in the game you still want people to book you for the old school shows and the reunion shows. You still want them streaming and buying your music, you know? You want them to remember the times when you were out here putting good work out.

In keeping the theme of your longevity, your sound is very deep and haunting. Sometimes it feels distant while being rooted in the samples that sit inside of it. You haven’t moved away from that when we’ve seen a lot of other cats move away from their sounds for whatever reason. What was it that made you stand on your peg and not succumb to the pressure of chasing a sound?

Boldy James: Because it’s my natural state. It’s how I like to work. It’s the type of beat selection I like to pick. It’s the type of bag I like to play out of. That always felt the most natural and the most normal to me. I just learned from listening to people like Al and Gunn to do what works for me. And try to be creative and switch it up but still stick to my guns for what makes the fans feel like they can relate to my music. Look what’s going on now. I got good recognition for being myself and not straying away from what I do.

Without jumping too far ahead, what does it feel like to be completely you while watching all of the wild shit that has happened in the game and now be the sound that everyone wants now?

Boldy James: It’s because most people run towards the club scene. They try to make turn up records. Me, I don’t make radio records. I don’t have a bunch of Instagram followers. It be eight to ten months where I’ll be locked out of my Instagram and shit. That’s not something that I needed to advance up the charts as much as being talented. People can appreciate that and they see me being myself and it makes them give themselves a reality check like, “Damn. The club is only open for a certain amount of time a day.” Muthafuckas ain’t in the club 24/7. You might be in the street but you not in the club 24/7. Me being in the street, I’m always high. I’m always chilling. I’m always paying attention to what’s going on. My music is more mild-mannered and laid back but it’s still street shit. As opposed to somebody trying to make a turn up record wanting everyone dancing and shaking their ass to the shit. When that’s really not always the energy. I try to reflect on normal shit.

Do you think this push for the club record comes from people really believing that tough niggas are the loudest that always want to be at the club and be seen?

Boldy James: No, it ain’t that. Niggas is trying to hit a lick. The club music is what’s getting the biggest feedback. Everybody wants everybody with their jewelry, Sunday’s best on, with money in their pocket having a dick swinging contest. This is the environment they want to be in. So that’s just the focus. They come in trying to hit a lick and be at the top of the game off the dribble. They don’t come in thinking they need to put in that work and build up a Boldy James buzz.

Something that I want to touch on that needs to be highlighted is the connection you have with the younger artist in your city. From the Beano’s, to the Drego’s, to the Sada Baby’s, you can name a list of cats you know or have worked with. Can you speak to having that base level recognition but also having that relationship with dudes that are from where you’re from minus the back biting that you see in so many other places?

Boldy James: I’m really active. I really be in the streets. On my musical journey I’ve seen cats come in the game, get a name, and fall off. I’ve seen cats come in the game, do they thing where as soon as they put a song out they making noise. I seen a couple of them fall off and get back on they deen. I’ve seen all those artists grow. I just know ‘em from me actually being active and involved in the inner city streets of Detroit. That’s how I know them. I come across all types of talent. Whether they make the type of music I make or not, I know a talented nigga when I hear ‘em. With that being said, I met Sada through my nigga Project. Me and Project used to hustle together and run the streets and get high together all day. I met Drego and Beano through my East Warren Mafia niggas. They some real street niggas. Run the East Side over there in my neighborhood. Everybody like to hang around them and shit. I grew up on the Warren so by default I know their families. We all know each other in the neighborhood.

But I say that to say this, a lot of things present themselves through the relationships I have through other people. Then when I meet these people they might have a respect for what I do, or being an OG street nigga, or I might have the studio that they working out of at the time, they might have seen me on MTV, working with Nas, or doing shows with Mac Miller. You know, people respect me for different reasons but they all respect me because I’m not the arrogant, fake, egotistical nigga who you gotta speak to first every time you see him. I’m a real nigga. I’m not just a self-proclaimed real nigga. All my people can vouch for this shit. Like, I got my nigga Darnell Williams with me right now. He from my neighborhood. He live out here in Cali working. He building a buzz up. He been doing his thing. But he’s my little brother from my neighborhood before all this shit. He used to work with Michael X and Illroots but no he’s carving his own name out in this shit. But I watched him grow from just trying to make a name and carve his name out to actually doing this shit. I respect it. It’s my little brother. He a real drug zone 7-6 nigga, Hunnedtown, Wish Bone. If you know where the little nigga come from and where he at now, you have to respect that. And that’s just what it is. I’m not too big for my britches. You ain’t gotta be no street nigga or killer for me to respect you. You just gotta be yourself.

Where do you think the disconnect is between the younger cats that are out here getting it and the older bitter niggas that are bitter that these youngins are getting it instead of recognizing that they’re making a way?

Boldy James: That’s because a lot of people be having an identity crisis. Not everybody is comfortable in their own skin. Me, I’ve never been threatened by nobody having the ups on me, or having more than me, or being better than me at something, or having a prettier girl, nicer house—that never bothered me. I always took that as people get what they got coming to them. Whether it’s good or bad. If that’s what God sees fit for that person to be doing with their life at that point in time then I’m all for it. I’ll always root the blessing on. It’s just most older cats can’t accept that they’ve wasted a lot of time and time has slipped out of their hands. They can’t get back that youth and they see the young guys do things that they’ve always wanted to do. In that respect, those things have never bothered me. Growing up I probably didn’t have the least out of my click but I for damn sure didn’t have the most. [laughs] You know what I’m saying? I can’t really complain about having anything or be bitter about what God blessed somebody else with. That’s just how I was raised. More niggas need to take that type of approach.